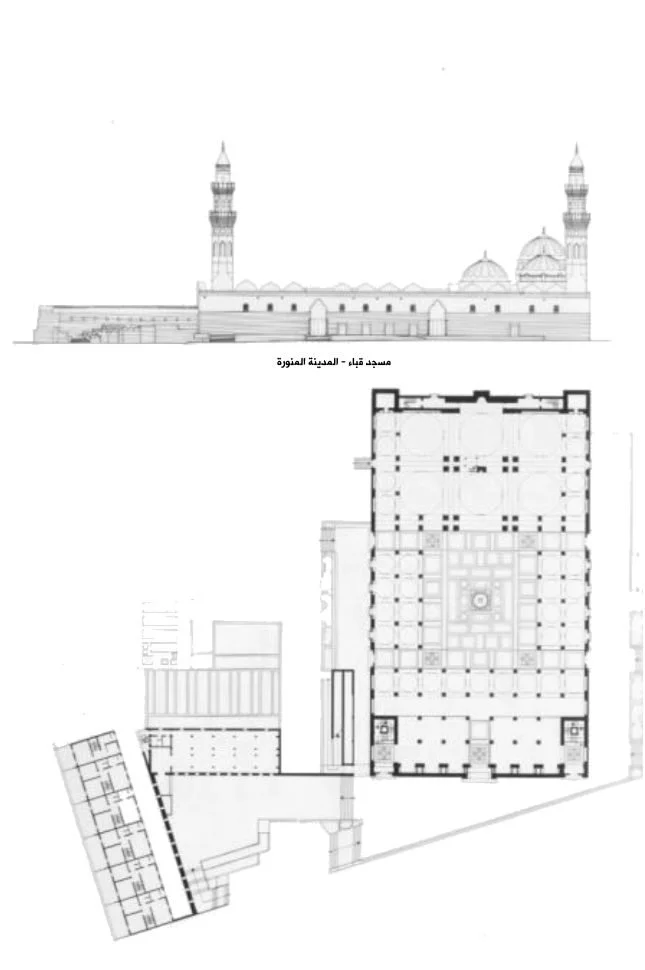

Masjid Quba in Madinah, Saudi Arabia

Masjid Quba holds the distinction of being Islam's first mosque, established in 622 CE when Prophet Muhammad (SAW) arrived at the outskirts of Madinah during his migration from Mecca. Located approximately six kilometers from Madinah's center in what was then the village of Quba, this mosque represents the foundational moment when the Muslim community transitioned from persecution in Mecca to establishing organized worship in Madinah. The Prophet (SAW) himself laid the mosque's first stones and physically participated in its construction alongside his companions, setting a precedent for communal effort in creating sacred space.

The current structure, completed in 1986 through a comprehensive reconstruction designed by Egyptian architect Abdel-Wahed El-Wakil, accommodates approximately 20,000 worshippers. While the building's form changed dramatically over fourteen centuries of renovations, the site's spiritual significance remained constant. The mosque is referenced in the Quran as a structure "founded on piety from the first day," and Islamic tradition holds that praying two voluntary prayer units (rak'ahs) here carries spiritual reward equivalent to performing Umrah (the lesser pilgrimage to Mecca).

Who Built Masjid Quba and Why?

The mosque's establishment directly relates to the Hijrah (migration), the pivotal event that marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar. In 622 CE, facing intensifying persecution from the Quraysh tribe in Mecca, Prophet Muhammad (SAW) and his companion Abu Bakr (RA) traveled northward toward Yathrib (later renamed Madinah). Historical accounts vary on the exact duration of their stay in Quba, with sources citing between 3 and 22 days, though 14 days appears most commonly in the traditions.

Upon arrival, the Prophet (SAW) stayed with Kulthum ibn al-Hadm (RA) of the Bani Amr ibn Auf clan. The site chosen for the mosque was reportedly a mirbad (a place for drying dates), and according to tradition, the Prophet's camel knelt at this specific location, indicating divine selection of the site. The Prophet (SAW) immediately initiated construction, personally placing foundation stones and carrying building materials on his back despite offers from companions to relieve him of the physical labor.

Al-Tabarani recorded an eyewitness account describing the Prophet's participation: "I saw the Prophet (SAW) when he constructed this mosque. He used to carry stones and rocks on his back until it was bent. I also saw dust on his dress and belly. But when one of his companions would come to take the load off him, he would say no and ask the companion to go and carry a similar load instead." This hands-on involvement demonstrated practical leadership and the principle that sacred work required personal investment regardless of status.

The original structure used simple, locally available materials: unbaked bricks (labina), palm trunks for structural support, and palm fronds forming the roof. This modest construction reflected the early Muslim community's limited resources and emphasized function over ornamentation. The building established a square or rectangular walled enclosure with an open central court. During the Prophet's lifetime, a roofed section supported by columns was added on the qibla side (the direction of prayer), creating the basic mosque plan that would influence Islamic architecture for centuries.

The mosque served multiple purposes beyond congregational prayer. It functioned as a community center where early Muslims gathered for consultation, education in Quranic recitation, and collective decision-making. Some sources identify Masjid Quba as the location where the first Friday congregational prayer (Salat al-Jumu'ah) occurred, though this remains debated among historians. What's certain is that the Prophet (SAW) established a pattern of visiting the mosque every Saturday, either walking or riding, to pray two rak'ahs, a practice that underscored the mosque's continuing importance even after Masjid al-Nabawi was built in Madinah proper.

What Makes Masjid Quba's Architecture Historically Distinctive?

The earliest architectural documentation describes a simple walled enclosure protecting an open courtyard, with a covered prayer area added during the Prophet's lifetime. This basic form established the courtyard mosque type (sahn) that would characterize much of Islamic architecture. The covered section featured columns (likely palm trunks in the original construction) supporting a flat roof of palm fronds, providing shade for worshippers while maintaining natural ventilation.

The mosque initially faced Jerusalem as the qibla, the direction Muslims faced during prayer. Approximately 16-17 months after the migration to Madinah, Prophet Muhammad (SAW) received revelation changing the qibla to face the Kaaba in Mecca. The Prophet likely rebuilt portions of Masjid Quba to reflect this new orientation, though specific architectural details of this modification are not preserved in historical sources.

Under Caliph Uthman ibn Affan (644-656 CE), the mosque underwent its first major expansion. During the Umayyad period, Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan ordered another expansion in 684 CE, followed by further rebuilding under al-Walid I (705-715 CE). The Umayyad structure at the time of Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz's renovations in the early 8th century was constructed from cut stone and lime mortar, with ceilings of valuable timber. This represented a significant material upgrade from the original palm construction, reflecting both increased resources and the mosque's elevated status.

Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz added the mosque's first minaret around 717-720 CE. This tower, used for the call to prayer (adhan), marked a shift toward standardized mosque components that would become universal in Islamic architecture. The minaret established visual prominence in the village landscape, announcing the mosque's presence and serving as a gathering point for the community.

In 1044 CE, Sharif Abu Ya'la Ahmad ibn Hasan added a mihrab (prayer niche) to the qibla wall. While the qibla direction had been marked since the revelation changing prayer direction toward Mecca, the formal niche provided an architectural focal point and improved acoustic qualities by projecting the imam's voice back toward worshippers. This addition reflected broader trends in Islamic architecture where the mihrab evolved from a simple mark on the wall to an elaborately decorated niche symbolizing the spiritual direction of prayer.

Throughout the Ottoman period, the mosque maintained what sources describe as its "generally Umayyad form," consisting of a covered prayer hall with an internal courtyard surrounded by galleries with rows of arches. Early 19th-century renovations under Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II replaced the flat ceiling with shallow domes supported by arches and columns. By the late 19th century, the mosque measured approximately 40 by 40 meters with ceiling heights around 6 meters, according to the writer Ibrahim Rifat Pasha's documentation.

How Does the 1986 Reconstruction Reflect Traditional Medinan Architecture?

The complete reconstruction initiated in 1984 under King Fahd ibn Abdulaziz fundamentally transformed the mosque's physical form while attempting to preserve its spiritual character. Egyptian architect Abdel-Wahed El-Wakil, a student of renowned traditionalist architect Hassan Fathy, received the commission to design a significantly enlarged structure. El-Wakil initially planned to incorporate the existing building into his design, but authorities decided instead to demolish the old structure entirely and construct a new mosque on the site. King Fahd laid the foundation stone on November 3, 1984, and the project reached completion on November 2, 1986.

El-Wakil's design philosophy centered on what architectural scholars call "traditionalism" or "revivalism," intentionally drawing from historical Islamic architectural precedents rather than pursuing modernist approaches. His training under Hassan Fathy emphasized indigenous construction methods and materials, principles El-Wakil adapted for the Quba project through extensive use of locally manufactured hollow clay blocks. Significantly, the construction avoided formwork concrete for major structural elements, instead relying on load-bearing brick walls supporting vaults and domes, a technique connecting the building to centuries of Islamic architectural practice.

The design references multiple traditions within Islamic architecture, particularly Mamluk, Seljuq, and Ottoman precedents. This eclecticism distinguishes El-Wakil's work from attempts to recreate a single historical style. Rather than producing archaeological reconstruction, the architect synthesized elements from various periods and regions to create what he considered an appropriately "Islamic" aesthetic for a 20th-century Saudi Arabian mosque.

The reconstruction expanded the mosque from its previous 40 by 40 meter footprint to a total site area of 40,780 square meters, with the ground floor covering 13,730 square meters. This dramatic increase in capacity responded to the growing number of pilgrims visiting Madinah and the mosque's integration into the expanded city (Madinah's growth had absorbed Quba village by the late 20th century). The design shifted from the previous square plan to a rectangular layout, with the prayer hall raised on a second-story platform.

The prayer hall features six large domes resting on clustered columns, creating the main worship space. The central courtyard is accessible from all entrances, facilitating circulation for thousands of worshippers. Four minarets occupy the corners of the mosque building, each rising from square bases through octagonal shafts that transition to circular forms as they reach the top. This minaret design follows traditional Ottoman conventions adapted to local Saudi Arabian contexts.

The courtyard is paved with tricolored marble: black, red, and white. During daylight hours, fabric screens cover the courtyard to provide shade from the desert sun, a practical necessity in a region where summer temperatures regularly exceed 40°C. Arabesque latticework on windows filters light entering from surrounding palm groves, creating patterns that recall historical Islamic decorative traditions.

Interior surfaces emphasize white marble, particularly in the mihrab and minbar. This material choice creates visual continuity while acknowledging the building's modern construction. The architects included Pakistani architect Hassan Khan Sayyid and Stuttgart tensile architect Mahmoud Bodo Rasch (a student of Frei Otto) in the design team, particularly for specialized elements like the courtyard shading structures.

The finished mosque includes comprehensive support facilities: residential areas for staff, administrative offices, ablution facilities, shops serving pilgrims, and a library. Seven main entrances and twelve minor entrances facilitate crowd flow, while 56 small domes surrounding the perimeter create the distinctive profile visible from distance. Three central cooling units provide air conditioning, a crucial amenity given the mosque's location and year-round use.

El-Wakil's work at Masjid Quba exemplifies debates within contemporary Islamic architecture about authenticity, tradition, and modernization. Critics note the tension between the architect's traditionalist philosophy and the complete demolition of the existing historical structure. The 19th-century mosque, while itself a renovation of earlier buildings, represented continuous architectural development at the site. Its replacement with an entirely new structure prioritized capacity and contemporary function over preservation of physical historical continuity.

How Does Masjid Quba Function in Islamic Devotional Practice?

The mosque's spiritual significance derives from both Quranic reference and prophetic tradition (hadith). Surah At-Tawbah (The Repentance), verse 108, addresses mosques built with different intentions, stating: "Never stand [to pray] there. A place of worship which was founded on piety from the first day is more worthy that you should stand [to pray] therein, wherein are men who love to purify themselves. Allah loves the purifiers." Islamic scholars traditionally identify this verse as referring to Masjid Quba, distinguishing it from Masjid al-Dirar, a rival mosque that hypocrites constructed nearby with intentions to divide the Muslim community.

Multiple authenticated hadith establish the spiritual merit of praying at Masjid Quba. The most frequently cited tradition records the Prophet (SAW) saying: "Whoever makes ablutions at home and then goes and prays in the Mosque of Quba, he will have a reward like that of an Umrah." This statement established a distinctive characteristic: unlike other mosques where reward relates primarily to the prayer itself, Quba's merit explicitly includes the journey to reach it, emphasizing intentionality and effort.

The Prophet (SAW) demonstrated this practice personally. As recorded in Sahih al-Bukhari, Ibn Umar (RA) stated: "The Prophet used to go to the Mosque of Quba every Saturday (sometimes) walking and (sometimes) riding." Another narration adds: "He then would offer two rak'ahs (in the Mosque of Quba)." This established Saturday visits as a recommended practice (sunnah), though not obligatory. Abdullah ibn Umar followed his father's example in maintaining this tradition.

For contemporary Muslims visiting Madinah, particularly during Hajj or Umrah pilgrimages, Masjid Quba represents a highly recommended but not mandatory stop. Pilgrims typically perform ablution (wudu) at their accommodations before traveling to the mosque, following the prophetic instruction literally. Upon arrival, they pray two rak'ahs of voluntary prayer, usually at the main prayer hall though any location within the mosque fulfills the tradition.

The mosque operates continuously, remaining open 24 hours daily to accommodate visitors arriving at different times. During Ramadan, visitor numbers increase dramatically as Muslims seek to maximize spiritual rewards during the sacred month. The mosque hosts special tarawih prayers (nightly prayers during Ramadan) and provides space for i'tikaf (spiritual retreat, particularly during Ramadan's final ten nights).

Beyond individual devotional practices, the mosque continues serving community functions. Local residents from the Quba area pray the five daily prayers there, maintaining the mosque's role as a neighborhood center. Educational programs, Quranic recitation classes, and religious lectures occur regularly, connecting the contemporary mosque to its original function as a space for community gathering and religious instruction.

What Is Masjid Quba's Relationship to Other Early Islamic Sites?

Masjid Quba exists within a cluster of historically significant locations in and around Madinah. After spending approximately two weeks at Quba, Prophet Muhammad (SAW) continued to Madinah proper where he established Masjid al-Nabawi (the Prophet's Mosque) adjacent to his residence. These two mosques, separated by six kilometers, bookend the Prophet's arrival in Madinah.

The houses of companions who hosted the Prophet and early Muslims at Quba no longer stand but their approximate locations are documented. Kulthum ibn al-Hadm's house, where the Prophet stayed, was situated on the southern side of the current mosque structure. Saad ibn Khaithamah's house, where other companions including Abu Bakr (RA), Ali ibn Abi Talib (RA), and several others lodged, stood nearby. These residential spaces formed the immediate context for the mosque, creating what was essentially Islam's first intentional community.

The site's contested relationship with Masjid al-Dirar adds historical complexity. The Quran explicitly condemns a mosque built by hypocrites "to cause harm, promote disbelief, divide the believers, and as a base for those who had previously fought against Allah and His Messenger." Historical sources, including Ahmad ibn Yahya al-Baladhuri, identify this condemned structure as having been constructed near Quba. Twelve hypocrites built it following directives from Abu Amir al-Rahib, who had rejected Islam and allied with Meccan opponents during the Battle of Uhud. Upon returning from the expedition to Tabuk in October 630 CE, Prophet Muhammad (SAW) ordered Masjid al-Dirar demolished. Some scholars suggest the current Masjid Quba either stands on the site of the destroyed mosque or very close to it, though this remains debated.

The connection to Masjid al-Qiblatain (the Mosque of the Two Qiblas), where tradition holds the qibla direction was first changed during a congregational prayer, provides another historical link. This event affected Masjid Quba as well, requiring reorientation of the prayer direction. The physical alteration of the building to accommodate the new qiblarepresented architectural manifestation of theological development, demonstrating how religious practice directly shaped built form.

What Does Masjid Quba Reveal About Early Islamic Architecture?

The mosque's development from simple palm-trunk construction to monumental stone buildings documents the material evolution of Islamic architecture. The original structure's emphasis on available materials and communal labor established practical precedents: mosques should be built within a community's means, construction should involve community participation, and function matters more than aesthetic elaboration.

The addition of specific architectural elements over time reveals how the mosque type developed. The original open courtyard with covered prayer area became the standard sahn plan. The addition of a minaret under Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz demonstrates how functional requirements (the need to call worshippers from distance) generated new architectural forms. The mihrab's later addition shows how symbolic representation of the qibla evolved from simple marks to elaborate architectural features.

The mosque's continuous renovation across dynasties illustrates Islamic architecture's principle of adaptive continuity. Rather than preserving buildings as historical artifacts, each generation modified structures to meet contemporary needs while maintaining sacred associations with the site. This practice prioritized use over preservation, emphasizing that a mosque's spiritual significance transcends its physical form. The Umayyad rebuilding in cut stone, Ottoman modifications adding domes and ornament, and Saudi reconstruction for mass pilgrimage each addressed specific historical circumstances while maintaining site identity.

The 1986 reconstruction's complete replacement of the previous building represents a modern departure from this pattern. Rather than modifying existing structure, authorities built entirely new construction. This approach reflects contemporary values around capacity, infrastructure, and architectural expression that prioritize designed coherence over historical accumulation. The decision to demolish rather than incorporate the 19th-century mosque reveals tensions between preservation as maintaining physical material and preservation as maintaining site sanctity.

El-Wakil's traditionalist design philosophy at Quba demonstrates another contemporary approach: using historical architectural languages to create new buildings that reference past forms without literally recreating them. This strategy attempts to bridge modernity and tradition by synthesizing elements from multiple historical periods. The resulting architecture looks recognizably "Islamic" to modern viewers through its use of domes, arches, geometric patterns, and calligraphy, even though it doesn't match any single historical prototype.

What Is Masjid Quba's Contemporary Significance?

For the global Muslim community, Masjid Quba maintains profound spiritual importance despite its architectural transformation. The site's association with Islam's foundational moment, the Prophet's direct involvement in its creation, and the Quranic and hadith references establish significance that transcends any particular building. When Muslims visit today, they connect not to the 1986 structure but to fourteen centuries of continuous worship at this location.

The mosque serves Saudi Arabia's religious tourism infrastructure, accommodating millions of visitors annually who combine Hajj or Umrah pilgrimages with visits to Madinah's historic sites. The expansion to 20,000-worshipper capacity and addition of modern amenities (air conditioning, expanded ablution facilities, accessibility features) enables this mass pilgrimage while raising questions about the relationship between heritage preservation and contemporary use.

The mosque's architectural approach influences broader debates about Islamic architecture in the contemporary world. El-Wakil's traditionalist methodology offers one answer to questions about appropriate design for Islamic buildings: looking backward to historical precedents while adapting them for modern requirements. This stands in contrast to modernist approaches that emphasize contemporary expression or attempts at literal archaeological reconstruction. Quba's design demonstrates both the possibilities and limitations of revivalism, creating recognizable Islamic aesthetic while acknowledging the impossibility of truly replicating historical construction methods or social contexts.

For architectural education, Masjid Quba provides a case study in heritage transformation. The site's evolution from 7th-century palm construction through successive stone rebuildings to 20th-century comprehensive reconstruction illustrates how sacred architecture balances continuity with change. The complete replacement of the earlier structure rather than its incorporation represents one approach to this balance, prioritizing functional requirements and aesthetic coherence over material preservation.

The mosque continues serving its original purpose: providing space for Muslims to worship collectively, connecting them to their faith's origins, and functioning as a community center for religious education and social gathering. Whether housed in simple palm structures or elaborate domed buildings, this fundamental function persists, suggesting that a mosque's essence lies in its use rather than its architectural form.

Glossary:

Hijrah -The migration of Prophet Muhammad (SAW) and early Muslims from Mecca to Madinah in 622 CE, marking the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

Mihrab - A niche in the qibla wall indicating the direction of prayer toward Mecca.

Minbar - An elevated pulpit from which the imam delivers Friday sermons.

Qibla - The direction Muslims face during prayer, toward the Kaaba in Mecca.

Rak'ah - A unit of Islamic prayer consisting of prescribed recitations and movements.

Sahn - The open courtyard of a mosque.

Umrah - The lesser pilgrimage to Mecca, which can be performed any time of year.